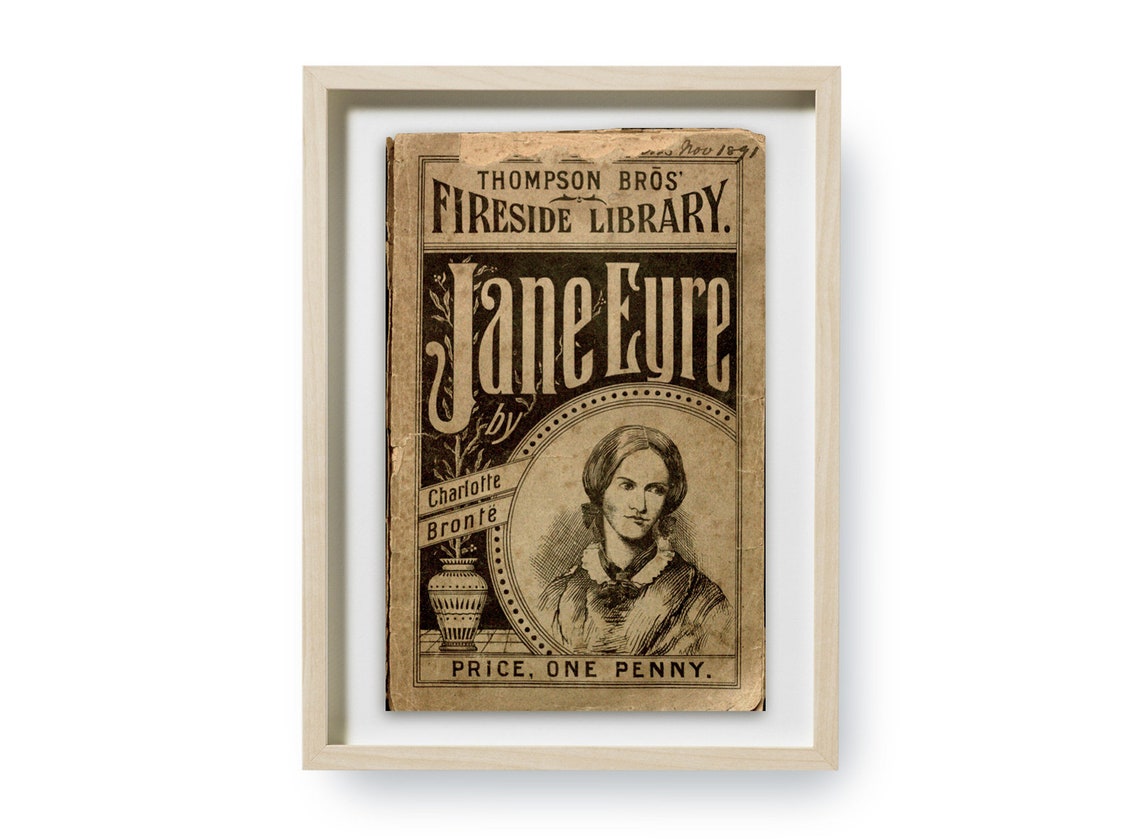

Charlotte Brontë, eldest of the Brontë sisters, a well-known Victorian author, and poet is best known for her books, the most famous of which is Jane Eyre (1847). After Jane Eyre’s popularity, Brontë, like her contemporaries Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Charlotte Brontë, experimented with the forms of poetry that would come to define the Victorian era—the extended narrative poem and the dramatic monologue. Included in this novel are the two songs by which most people now are familiar with her poetic work. One of the most notable examples of this transition in taste and marketability is Charlotte Bronte’s choice to switch from producing poetry to writing prose fiction in the late 1830s and early 1840s. A poet’s experience in the early Victorian literary culture reflects these developments and shows how important she was in the history of 19th-century writing.

Bronte was born in Thornton, West Yorkshire, on April 21, 1816. As the son of a well-to-do Irish farmer in County Down, her paternal grandfather was Patrick Brontë. After becoming a schoolteacher and tutor and attracting a local patron’s notice, Patrick was accepted into St. John’s College at Cambridge in 1802 to study the classics; he would have been expected to manage the land he was to inherit. A year after graduating from college in 1806 and receiving his license as a priest in the Church of England, he married. Aside from the sermons that he wrote and delivered frequently, Patrick Brontë was also a modest poet who published his first collection of poems in 1811. After starting off in a less-than-ideal situation, he rose above it all thanks primarily to his natural skill and dedication, attributes that his daughter Charlotte undoubtedly acquired as well.

Maria Branwell Brontë, Charlotte’s mother, died when she was just five years old. After marrying Patrick Brontë in 1812 and having six children in seven years—Maria (1813), Elizabeth (1815), Charlotte (1816), Patrick Branwell (1817), Emily (1818), and Anne (1820)—Mary Branwell, the daughter of a wealthy tea trader and grocer, passed away from cancer at the age of 38. All four Brontë children—Charlotte, Branwell, Emily, and Anne—were impacted by their mother’s death, although the younger three—Charlotte, Branwell, and Emily—were not. After reading letters that her mother sent to her father during their courting and realizing she hadn’t known her, Charlotte wrote to a friend on February 16th, 1850, “I wish She had lived and that I hadn’t known her.”

She arrived from Penzance to care for the family while Maria Brontë was unwell, and she stayed until Patrick Bronte’s attempts to remarry following his wife’s death were fruitless. Charlotte Bronte’s close friend Ellen Nussey described her as “lively and intellectual” and “capable of debating without fear.” Despite the stereotypes of “Aunt Branwell,” she was a “bright, lively, and clever” woman who was capable of arguing “without fear” with her brother-in-law. After arriving in Haworth as a new aunt, she appears to have exerted a greater influence on Anne, who was just a few months old at the time. In addition to playing on the vast moors around their parsonage house, they read voraciously and indulged in the creative play that would swiftly evolve into literary ingenuity when they were left to their own devices on many occasions.

Maria, Charlotte’s eldest sister, appears to have had a particularly positive impact on her siblings’ artistic growth. In the aftermath of her mother’s death, Maria, an unusually mature nine-year-old, began reading to her father and siblings from the pages of Blackwood’s Magazine. In addition, she staged little plays in which the children learned to speak in the voices of imaginary characters at an early age. Like her younger siblings, Charlotte was drawn to the world of literature at a young age by her father’s guidance and Maria’s support.

Charlotte and Emily were eight years old when they enrolled at the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge in Tunstall in 1824. Cowan Bridge had a lot to recommend it to Patrick Brontë, notwithstanding Charlotte’s famed portrayal of “Lowood School” in Jane Eyre. As a “necessary cleric” with five daughters and one son, he would have considered the school’s goal to be in line with his aspirations for his daughters’ education. Leeds Intelligencer, December 1823: The school’s goal was to give young women the “plain and useful Education” they needed to “maintain themselves in the different Stations of Life to which Providence may call them,” as well as “a more liberal Education for any who may be sent to be educated as Teachers and Governesses.” Since their father was deeply concerned about the well-being of his four eldest daughters, Patrick Brontë made the decision to send them to Cowan Bridge. This decision was passed down to Charlotte, who was the most concerned about finding a career that she could be happy in while also making a decent living.

Charlotte Bronte’s first memories of school life would have made teaching a dreadful career choice for the novelist. For example, Juliet Barker points out that her ability to read and write indifferently, cipher [arithmetic] a bit, and sew (in a nice manner) is all that is recorded in the school register in The Brontë (1994). ‘Knows nothing of Grammar or Geography or History, or of their own accomplishments’ In terms of Charlotte, the register tells us little, but it does suggest that Cowan Bridge was unlikely to notice particular ability, much less cultivate it. “Altogether intelligent for her age, but knows nothing methodically,” is the evaluation’s concluding statement.

Boarding school life was extremely difficult for Charlotte, who found it to be a grueling experience. Many pupils were compelled to leave the school due to epidemics of “low fever,” or typhus, which was spread in an unhygienic manner and led to their deaths. Maria suffered a severe case of consumption while staying at Cowan Bridge and was subjected to harsh treatment by Miss Scatcherd, which Charlotte used as a basis for her depiction of Helen Burns’s martyrdom in Jane Eyre. It wasn’t until Patrick Brontë learned of Maria’s illness in February 1825 that he was able to remove her from school, and she died at home in early May as a result. Elizabeth, on the other hand, had been struck down with a serious illness. Elizabeth was led back to Haworth two weeks after Charlotte and Emily were returned home by their father on June 1 when the entire school was transferred to a healthier location by the sea on doctor’s instructions.

Charlotte’s life was significantly impacted by the deaths of Elizabeth and Maria, who are likely to have had a significant impact on her personality as well. After losing her mother at an early age, she was thrust into a position of leadership and was left with a sense of responsibility that she struggled to reconcile with her natural tendencies toward rebellion and self-improvement. This was the turning moment in Charlotte’s leadership of the family’s activities, and it was one she would hold onto for the rest of her siblings’ lives and literary careers.

At home, Patrick Brontë instructed his four remaining children and hired qualified tutors to teach them music and painting following the awful incident at Cowan Bridge. In addition to Charlotte’s guidance, the youngsters read voraciously on their own and engage in imaginative play. From their father’s library, they could select from a wide range of books, including the Bible, Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan, Moral Sketches by Henry Hudson, and The Seasons by James Thomson. They were also given the freedom to read anything they wanted, as long as it was in accordance with their parents’ preferences. Charlotte and Branwell’s early writing was highly affected by Blackwood’s Magazine, which the family read on a daily basis, as was Fraser’s Magazine For Town and Country, which began publishing in 1832 and was equally vibrant and important in its emphasis on literature. One or more of the Brontë’ local circulating libraries may have held popular current novels and poems, as evidenced by their access to the Ponden House library, which is located nearby.

On June 5, 1826, Mr. Brontë arrived from Leeds with a gift for Branwell—a box of toy soldiers—and all four Brontë children quickly lay claim to it. This was a watershed moment in their literary apprenticeship. As each youngster chose a soldier to represent him or herself, they proceeded to create dramas and tales around and through the voices of these characters, calling them after their favorite childhood heroes. The earliest examples of this genre were written by toy soldiers in miniature manuscripts with tiny, nearly microscopic handwriting.

The Duke of Wellington’s two sons, Charles and Arthur Wellesley, and the social elite of “Glass Town,” eventually changed into the kingdom of “Angria,” are the focus of Charlotte Bronte’s juvenile tales. As a Byronic hero, Arthur, soon elevated to “Duke of Zamorna,” engages in both romantic and political treachery; his younger brother Charles, a less powerful and often humorous figure, is a spy and reports on the scandalous activities of his Angrian compatriots—especially Arthur and his many paramours. Aside from the fact that Bronte’s handsome, but morally repugnant Duke of Zamorna becomes the family poet, it is noteworthy that Charles Wellesley is the family storyteller and her favorite person to tell stories.

As well as providing insight into Bronte’s early explorations of themes that would later appear prominently in her adult works, such as romantic passion and sexual politics, desire, betrayal and loyalty as well as vengeance, these tales also reveal her awareness of a topic that was prevalent in Victorian literary culture at the time: the idea that poetry writing was a frivolous and even immoral pursuit. Bronte’s “self-concentered” poet-duke is one way she symbolizes her own early uncertainty about being a poet since he is both romantically appealing and destructively narcissistic. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Robert Browning, and Matthew Arnold were all-male Victorian poets who felt conflicted about female subjectivity, and this conflict was exacerbated later in society by societal rules against it.

For all, as the Brontë’ works as children have been likened to fantasies, they were not only uneducated speculations on the part of the authors. “A Romantic Tale,” dated April 15, 1829, shows that the young writers were familiar with articles on British colonizing in Africa published by Blackwood’s Magazine in 1826 as well as more expected sources, such as the Bible, Bunyan’s works, standard educational texts like J. Goldsmith’s Grammar of General Geography (1825), the Arabian Nights Entertainments and Tales of the Genii (1820) by Sir Cha (pseudonym of James Ridley).

With their knowledge of real-life military conflicts like the Peninsular War, 1808–1814, these characters discuss current events like the Catholic Emancipation Act and political gossip about notable persons like the Duke of Wellington. It is an homage to popular oriental cityscape paintings by John Martin, and the Angrians are based on contemporary engravings that Charlotte meticulously copy from popular annuals such as The Literary Souvenir, as well as books like Finden’s Illustrations of the Life and Works of Lord Byron (1833–1834).

As soon as Charlotte took over as editor in 1829, Branwell began “editing” Branwell’s Blackwood’s Magazine, which was renamed Blackwood’s Young Men’s Magazine. The two worked together to produce miniature hand-sewn volumes that closely resembled the original Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. Both Charlotte and Branwell’s magazines feature a variety of works, including fiction and nonfiction in a variety of forms and styles. They also include advertising and editorial comments regarding the publishing of the magazine as well as information about how it is distributed and how it is sold. Charlotte and Branwell re-created the material form of Blackwood’s Magazine, engaging in literary gossip and conflicts similar to those they had read about in their reading, and they filled their narratives with literary evaluations and vituperative personal conversations between Glass Town literati.

Charlotte Brontë originally dabbled with poetry at this early time of lighthearted but profound engagement in make-believe literary life. In the years 1829–1830, the 14-year-old made a concerted effort to establish herself as a poet by penning 65 poems and a satirical play about the craft. Most early poems have a Glass Town setting, since they are interwoven in her stories and spoken or sung by fictional characters, while some only weakly link with the stories. They shed light on Bronte’s knowledge of current literary controversies, such as “neglected talent,” the importance of tradition and imitation against originality and inspiration, and how poetry is received by the audience in a changing literary economy. By mimicking past poets, Brontë developed her own poetry style throughout this period of self-imposed training. James Thomson and William Wordsworth, two of the so-called “nature poets,” are to be credited with the development of topographical poetry in the 18th century. Bronte’s many poetry presented as songs shows the influence of the well-known Thomas Moore.

In “The Violet,” dated November 14, 1830, Brontë purposefully mimics Thomas Gray’s “Progress of Poetry” (1754), in which she chronicles the history of Western literature beginning with Homer and then begs for membership to that “bright band” of poets who have preceded her:

Hail army of immortals hail! Oh Might I neath your banners march! Though faint my lustre faint & pale Scarce seen amid the glorious arch Yet joy deep joy would fill my heart Nature unveil thy awful face To me a poets pow’r impart Thoug[h] humble be my destined place

Bronte’s lyrical inexperience and excitement for her chosen profession are evident in this early poem. Other works by Brontë demonstrate her capacity to laugh at her own literary pretensions. “such a lovely dogge[re]l / as this was never written / not even by the powerful / & exalted Sir Walter Scott,” she closes one of her lushly descriptive poems.

A lyre-playing bard and other Romantic poet-figures can be found in Bronte’s early poetry, but her novels and plays frequently mock the romantic notion of the poet as a unique genius. The Poetaster,” a fiction dated July 6–12, 1830, features Henry Rhymer, a parody of herself and her siblings’ amorous escapades, in order to disprove them. Also, in the 1830s, when printing technology-enabled for a slew of new authors to break into the literary market, “The Poetaster” satirizes England’s rapidly shifting literary climate. Every youngster that goes down the street with their manuscripts in hand, going to the printers for publication, will be seen as a disgrace to the “great profession [of authoring],” laments a Glass Town publisher. In making light of her own and her siblings’ early literary ambitions, Charlotte Brontë demonstrates a wry understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of pursuing a literary career in the nineteenth century.

In January 1831, Brontë left Haworth for a second time, this time to attend Roe Head School in Mirfield, a town near Dewsbury, some 20 miles away. Roe Head was a tiny school operated by Margaret Wooler, whose father described her as an “intelligent, nice, and motherly woman.” With just approximately seven boarding students at a time, all roughly the same age, the school was able to pay particular attention to each student’s specific needs and talents. Even though Brontë was initially homesick and isolated from the other students due to her differences from them—her outdated dress, slightly eccentric behavior caused by poor eyesight and timidity, and her ignorance of grammar and geography, in addition to her precocious knowledge of literature and the visual arts—she eventually won the respect and affection of her peers and came to feel quite at home in her new school environment.”

Bronte had two distinct yet long friendships during her time at Roe Head. Throughout her life, Bronte corresponded with Ellen Nussey, a totally traditional and lovingly faithful girl. She edited her friend’s letters significantly after her death in order to protect her friend’s reputation. Mary Taylor, another close friend of Bronte’s, was as bit the extremist as Nussey. Boisterous, brilliantly articulate, and more intellectual than Nussey Taylor, Brontë may have found Taylor appealing because of her bright, rebellious, and ambitious side. She then wrote The First Duty of Women (1870), in which she suggested that women should first focus on preparing themselves for financial independence. When she arrived in New Zealand in 1845, she took action on this conviction by starting a profitable shop and running it until she returned to England in 1860, where she lived out the rest of her life in relative luxury. It’s a shame that just one of Bronte’s numerous letters to Taylor has survived.

After arriving at the school a long distance behind the other girls, Brontë rapidly rose to the top of her class and remained there for the next 18 months, winning several awards and medals for her academic excellence. Brontë often continued her studies after school while the other students were having fun, indicating that she saw school as an investment in her future: she wasn’t going to Miss Wooler’s only to get her nails polished, but also to learn how to be a governess. She barely composed three poems when she was in school since she was so focused on her schoolwork.

Eventually, Brontë returned to the exhilarating world of Angria and the activity of writing after her departure from Roe Head in May 1832. She was in charge of her younger sisters’ schooling at Haworth. She penned 2,200 lines of poetry between 1833 and 1834, much of which was woven into her and Branwell’s passionate stories about the political and amorous adventures of their beloved Angrians. Singing a lyric is an art form that necessitates an understanding of not just what is being referenced but also who is singing it and where they are in time and space. The Angrian story is further expanded in other poems, which complicate and enrich the themes of the accompanying prose novels. The poems she wrote previously to her time at Roe Head are more technically skilled, but they also reflect a greater focus on the people and subject of the stories and less desire to experiment with poetic form. Branwell’s military war and Charlotte’s romantic treachery became the major focus of her fantasy novels, while her literary self-reflectiveness faded away in favor of almost complete immersion in the Angrian realm of fiction.

“All that is written in this book must be in a decent, straightforward, and readable hand,” her father wrote in the preface to a series of poems written in normal-sized script on lined paper, which appears to be from the same notebook. PB.” For example, in “Richard Coeur de Lion & Blondel,” “Death of Darius Codomanus,” and “Saul,” three non-Angrian poems, it appears that Bront saw the necessity to construct a public poetic style to go along with the private writing she and her siblings enjoyed in their creative dreams. That Bronte’s poetry reveals a struggle to reconcile her private life with a small group of close friends and family members with her public life of obedience to father figures and teachers is an important clue to understanding the poet’s inner turmoil (the poems on historical and Biblical figures are similar to school exercises she later wrote in Brussels). Even after gaining considerable poetic skill and overcoming a great deal of worry over this apparent contradiction between the allure of the private imagination and the obligation of public responsibility, this split finally prompted Brontë to forsake poetry and turn to prose fiction.

When Bronte was hired as a teacher at Roe Head as a replacement for Miss Wooler in July of 1835, she was concerned that she would not have the opportunity to act out her Angrian stories. When it came to her “wretched bondage” to the teaching profession, Bronte’s notebook shows that she was growing more and more bitter. Her productivity during this time period was far lower than that of her boyfriend Branwell, who had set up shop in a Halifax studio with the goal of making a career as a portrait painter and had plenty of spare time to write and socialize with his other writers.

When Brontë returned to Roe Head, her poems express her sorrow for home and Angria, as well as her nervous need to combine her ambition to write with the requirement of teaching to earn a living. “Retrospection,” one of the best-known of these poems, opens with a powerful recollection of one’s past.

We wove a web in childhood A web of sunny air We dug a spring in infancy Of water pure and fair We sowed in youth a mustard seed We cut an almond rod We are now grown up to riper age Are they withered in the sod …

For the next 177 lines, the poem depicts the Duke of Zamorna in more detailed settings. This is interrupted by “a voice that dissolved all the enchantment” when one of her students “throw[ed] her small rough black head into [her teacher’s] face” to ask, ‘Miss Bronte, what are you thinking?’ A stunning illustration of the discrepancy between the inner, imaginary life of Charlotte Bront and her real experience at Roe Head, as described in the novel.

Slowly, but surely, Brontë was able to pick up the speed of her writing to that of her earlier, more prolific periods, but even then, there is evidence of her being distracted and dissatisfied. For example, her tales from 1836 demonstrate that she was frequently unable to decide on a theme or locate new things to write about, and many poems from this era finish abruptly or drift off rather than drawing to a close. Bronte’s longing for romantic, social, and intellectual stimulation, which she linked with the fictional realm of Angria and in particular with her poet-duke, who appears in the poem as an intriguing literary muse, is evident in poems like “But Once Again…,” dated January 19, 1836.

I mean Zamorna! … he has been a mental King That ruled my thoughts right regally And he has given me a steady spring To what I had of poetry. … I’ve heard his accents sweet & stern Speak words of kindled wrath to me When dead as dust in funeral urn Sank every note of melody And I was forced to wake again The silent song the slumbering strain. … to his altar I am bound For him the consecrated ground My pilgrim steps have trod … grovelling in the dust I fall Where Adrian’s shrine lamps dazzling glow …

It wasn’t until December of 1836 that Brontë made the decision to try her hand at professional writing in the hopes of making money as a published poet. Then poet laureate of England Robert Southey, whom she submitted a selection of her poems to, was her go-to source for guidance. His letter of March 12, 1837, in which he received this disheartening response, has since become legendary:

Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life: & it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure she will have for it, even as an accomplishment & a recreation. To those duties you have not yet been called, & when you are you will be less eager for celebrity.

There’s little doubt that Brontë was moved by Southey’s advice, as evidenced by her response and the fact that she retained his letter in an envelope imprinted with the words “Southey’s Advice | To be kept forever.” As of July 1838, Bronte had penned more than 60 poems and verse fragments, many of which would become some of her most famous compositions. In 1845, however, she was finally able to rework them into poetry that she was comfortable putting out into the world.

In December of 1838, Brontë left Roe Head for good and spent the next four years trying to find a way to earn a livelihood while continuing to write in Haworth. Between May and July of 1839 and March to December of 1841, she worked as a nanny for two families in the Rawdon area: the Whites at Upperwood House in Rawdon and the Sidgwicks in neighboring Lothersdale. Both of her attempts ended in failure due to her inability to adapt to the circumstances. She told Nussey the following on March 3rd, 1841:

… no one but myself can tell how hard a governess’s work is to me—for no one but myself is aware how utterly averse my whole mind and nature are to the employment. Do not think that I fail to blame myself for this, or that I leave any means unemployed to conquer this feeling. Some of my greatest difficulties lie in things that would appear to you comparatively trivial. … I am a fool. Heaven knows I cannot help it!

Aunt Branwell loaned her money in the summer of 1841 so that she and her sisters could open a school. As a result, she turned down the generous offer made by Miss Wooler in December to take over as director of Roe Head School, a prestigious institution already well-established in the community. A new and more exciting plan suggested by Mary Taylor explains this egregiously bad business decision: she and Emily were going to go to school on the Continent to improve their French and Italian language skills and gain “a dash of German” to attract students to the school they would open when they returned. On September 29, 1841, Brontë sent a letter to Aunt Branwell in a self-confident tone, inspired by Taylor’s descriptions of Europe and bolstered by the presence of the Taylors in Brussels, where she planned to study.

I feel an absolute conviction that, if this advantage were allowed us, it would be the making of us for life. Papa will perhaps think it a wild and ambitious scheme; but who ever rose in the world without ambition? When he left Ireland to go to Cambridge University, he was as ambitious as I am now. I want us all to go on. I know we have talents, and I want them to be turned to account.

It was in February 1842 when Charlotte and Emily Brontë left England and enrolled as the eldest pupils in a school established by Madame Claire Zoe Heger and her husband Constantin Heger. When the Bronte sisters were students in a Roman Catholic Belgian boarding school, their disparities in language, culture, age, and faith made it difficult for them to connect with their contemporaries. When the two young ladies returned to Haworth for Aunt Branwell’s burial in November of 1842, Emily elected not to return to Brussels, despite the fact that she had made substantial scholastic progress there.

Charlotte Bronte, on the other hand, found the Pensionnnat Heger more than just a place to study; rather, it was a place where she could meet and fall in love with Constantin Heger. In contrast to Southey, he was an exceptional literature instructor who pushed Brontë to sharpen her writing talents while also helping her explain her thoughts on the craft of writing. Heger’s guidance prompted Bronte to revisit the literary challenges she first addressed in her early poems with a renewed feeling of urgency. Heger’s neoclassical principles of control, study, and imitation were a counterpoint to her Romantic concentration on lyrical “genius,” which generates without effort. When Bronte was younger, he didn’t just dismiss Romantic ideals about genius and lyrical originality; rather, he took such arguments seriously and painstakingly stressed the need for technical competence and precise workmanship in her writing.

Brontë continued to transcribe amended versions of her previous poems into a copybook she carried with her from Haworth, even though she didn’t appear to be writing any new poetry during her time in Brussels. This suggests she was thinking about publishing them at some point in the future. Motivated as never before, Charlotte Bronte’s admiration for Heger swiftly turned into an intense romantic attraction for the man who she described in an open letter she sent on July 24, 1844, as “my literature master… the only master that I have ever had.” Because of her husband’s fascination with his English student, Madame Heger quickly sought to establish some distance between the two of them. Rejecting the Belgian school and returning to England, Bronte withdrew from the institution in January 1844.

Bronte’s letters to Heger in 1844, sent from Haworth, brutally show her affections for “Monsieur,” while also revealing her growing worry about finding a meaningful career path for herself. Since her nearsightedness had always been a problem for her, she was forced to admit to Heger, a bit histrionically, that “a literary profession is closed to me — only that of teaching is accessible to me” since too much writing would lead to blindness. In November, the Bronte sisters decided to abandon their plans to create a school in Haworth since no one had answered their adverts for students. It looked as if the future for the eldest Brontë was bleak on all fronts, especially romantic, professional, and literary.

Emily’s poetry saved Brontë from deep despair in the fall of 1845, when she discovered a notebook of Emily’s work. According to her “Biographical Notice” to the 1850 edition of Wuthering Heights, these were not “ordinary effusions, nor at all like the poetry ladies typically compose.” She pushed her sister to publish a collection of her poetry, which included some of her own writing as well as some of Anne’s. Emily and Anne Brontë may have insisted that the poems be published under pseudonyms, and Charlotte Brontë set out to find a publisher for the collection of poems, Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell (1846). Aylott & Jones, the small London publisher, agreed to print the collection at the authors’ expense, a common practice for unknown authors.

“The simple endeavor to succeed had given a magnificent zest to live; it must be pursued,” Charlotte Bronte later wrote in the “Biographical Notice.” She happily accepted sole responsibility for dealing with their publisher and seeing the Poems through the press. While she may not have been as successful as her contemporaries, like her future biographer Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell, in the early Victorian English literary economy, her enthusiasm for both the business and creative aspects of authorship demonstrates her determination to succeed as a professional author there. After 1845, her poetry output was practically nonexistent, while she was already working on her first book, The Professor when the Poems were published in 1857.

Unlike her sisters, Charlotte Bronte’s poetry in the 1846 collection is almost all revisions of older works, primarily from the productive era of 1837–1838, which she reworked specifically for publication in this volume. It was Bronte’s way of adapting her works to a new audience, using popular themes and conveying feelings that were culturally relevant at the moment (such as in “The Wife’s Will”) but also erasing any connections to their original narrative settings. Tennyson, for example, uses words from “Pilate’s Wife’s Dream” (originally a hypothetical monologue uttered by the Duchess of Zamorna in a totally different imaginary setting) to predict the ultimate assertion of faith articulated in In Memoriam (1850):

I feel a firmer trust--a higher hope Rise in my soul--it dawns with dawning day; . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ere night descends, I shall more surely know What guide to follow, in what path to go; I wait in hope--I wait in solemn fear, The oracle of God--the sole--true God--to hear.

In 1846, Brontë published a series of poems that she had reworked to fit the context in which they were published—a clear indication that Bronte had begun to adapt her idealistic conceptions of literary talent to the demands of professional authoring.

To keep the collection balanced, Charlotte Brontë contributed just 19 of the sisters’ 21 poems, so that each writer had almost the same amount of space. “Currer,” “Ellis,” and “Acton” are explicitly identified as poets in each poem. The three poets’ contributions appear in alternating order, such that no one poet dominates any piece of this collection. The result makes Emily’s excellence as a poet more apparent by drawing comparisons between the three writers.

It also obscures coherence amongst Charlotte Bronte’s poems, many of which are linked by ongoing storylines and/or by consistent character traits. “The Woman’s Will,” “The Wood,” “Regret,” and “Apostasy” are four poems that collectively tell the narrative of an English wife who decides to accompany her husband into political exile in France, where she declares her commitment to her home faith, the religion of passionate love:

’Tis my religion thus to love, My creed thus fixed to be; Not Death shall shake, nor Priestcraft break My rock-like constancy!

Four dramatic circumstances in which the speaker addresses an implicit audience—William in the first three poems, and a French-Catholic priest in the last—are used to develop her character via long monologues. Both the extended narrative poem (such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1857)) and the dramatic monologue (probably the most uniquely Victorian poetry form, honed by writers such as Tennyson and the Brownings) may be found in these poems. “Frances,” “The Missionary,” “Pilate’s Wife’s Dream,” and “The Teacher’s Monologue” are some of the other Brontë monologues.

The poems “Evening Solace” and “Winter Stores,” for example, are plainly lyrical, although the majority of Bronte’s poems include a narrative component. Jane Eyre’s Gothic components may be seen in her narrative poems like “Gilbert,” “Mementoes,” and “The Letter,” as well as in Tennyson’s “Mariana,” which uses exact imagery and specifics of the location to transfer a character’s state of mind into his or her exterior world. “Preference” seems to be an indignant woman’s response to the aggressive declaration of love asserted by the male speaker of her preceding poem, “Passion,” and “Gilbert” seems to be exactly the kind of arrogant lover who seduced and betrayed “Frances,” whose troubled monologue precedes the story in which he is brought to retributive justice (though his victim is identified as “Elinor”).

In addition to their common origins in her childhood writings, Charlotte Bronte’s published poems share a formal similarity based on a new purpose in her writing: to develop characters who are psychologically interesting through monologues and narratives that reveal personality within the context of dramatic situations. Bronte’s poetry of 1846 is therefore connected both to the prominent literary forms of the Victorian era—the lengthy narrative poem and the dramatic monologue—and to the literary form by which she was finally recognized as an author in the public sphere: the novel.

There were only two copies of Poems sold in the first year of publication despite Bronte’s efforts to promote the book, which included paying for advertising and instructing Aylott and Jones to send review copies to fourteen magazines. Originally published in 1848 for four shillings, Gaskell’s 1857 biography of Charlotte Brontë sparked renewed interest in the work after it was reissued by the publishers of Jane Eyre. Many critics have lauded Emily Bronte’s poetry, but when Jane Eyre was selling well, a few of the Britannia’s reviews from the years 1848 to 1849 praised Charlotte Bronte’s poetry instead. For example, the anonymous reviewer on November 10, 1849 praised her “mastery in the art of word painting” and “faculty of exhibiting in words the shadowy images of mental agony.” ES Dallas, writing in Blackwood’s Magazine in July 1857, noted that her poetry is distinct from her sisters’ because of her “facility of forgetting herself, and talking of things and persons exterior to herself”—a quality shared by novelists and poets who write narrative and dramatic monologue forms. In contrast, in an 1850 letter to Gaskell, Brontë vehemently agreed with those who believed her sister’s poetry was superior, and she disregarded her own contributions to the 1846 collection as “juvenile products; the restless effervescence of a mind that would not be quiet.”

Brontë mailed copies of Poems to a number of notable literary people in 1847, a standard tactic for aspiring authors who wanted to get the notice of famous reviewers. To no avail, she attempted nine times to get her debut novel The Professor published before receiving an encouraging response from Smith, Elder, who denied publishing it but requested to evaluate any future works of fiction she might be working on. Bronte completed Jane Eyre approximately two weeks after receiving this request and was pleased to see the work in print soon afterward. “Currer Bell,” the author of Jane Eyre, swiftly became a household name after the book’s release.

Only three unfinished poems commemorating her sisters’ deaths were written by Brontë after the publication of her novel’s popularity. However, despite her deep grief over the sudden deaths of Branwell (on September 24, 1848), Emily (19 December 1848), and Anne (on May 28, 1849), she continued to publish novels like Shirley and Villette, as well as engaging in literary correspondence with a number of notable figures like George Henry Lewes and William Smith Williams, the firm’s perceptive and kind reader. Allowing her name to be known, she acquired the literary renown that Southey had urged her to avoid and met a number of notable authors, including William Makepeace Thackeray, Harriett Martineau, and Elizabeth Gaskell, among others. She married Arthur Bell Nichols, a curate of her father’s, at the age of 38, and died on March 31, 1855, likely of hyperemesis gravid arum (extreme vomiting during pregnancy) or a major illness of the digestive tract. Except for Anne, who passed away in the seaside resort of Scarborough, the remainder of her family is interred at the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, directly across the street from her parsonage house.

In her own time, Charlotte Brontë was not a popular poet, and now she is most recognized for her novels rather than her poetry. There will always be a negative connotation associated with Emily’s poetry due to the unavoidable parallels to her sister’s more discursive approach. In terms of poetic monologues, Pilate’s Wife’s Dream and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s well-known “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” are both excellent examples. One reason Bronte is so essential to poetry’s history is that her career shows how literary preferences changed from poetry to prose fiction and how she used the poetic modes that were commonplace in the Victorian age.

As Virginia Woolf claims in “Jane Eyre” and “Wuthering Heights,” readers read Charlotte Bront’s works “for her poetry,” one might make the case that Bront never completely abandoned her vocation as a poet. So that she might become a successful literary professional in Victorian England and a recognized “major author” in British literature’s approved canon, Bront adapted her creative impulses to the market’s expectations.

References: Christine Alexander, The Early Writings of Charlotte Brontë(Oxford: Blackwell, 1983).

Miriam Allott, The Brontës: The Critical Heritage(London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974).

Carol Bock, “Gender and Poetic Tradition: The Shaping of Charlotte Brontë’s Literary Career,” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, 7 (1988): 49-67.

Sue Lonoff, “Charlotte Brontë’s Belgian Essays: The Discourse of Empowerment,” Victorian Studies, 32 (1989): 387-409.

Virginia Woolf, “‘Jane Eyre’ and ‘Wuthering Heights,'” in her The Common Reader, first series (London: Hogarth Press, 1925), pp. 196-204.

BOOKS Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, by Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë (London: Aylott & Jones, 1846; Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1848).

Jane Eyre. An Autobiography, as Currer Bell (3 volumes, London: Smith, Elder, 1847; 1 volume, New York: Harper, 1847).

Shirley: A Tale, as Currer Bell (3 volumes, London: Smith, Elder, 1849; 1 volume, New York: Harper, 1850). Villette, as Currer Bell (3 volumes, London: Smith, Elder, 1853; 1 volume, New York: Harper, 1853).

The Professor: A Tale, as Currer Bell (2 volumes, London: Smith, Elder, 1857; 1 volume, New York: Harper, 1857).

The Twelve Adventurers and Other Stories, edited by C. K. Shorter and C. W. Hatfield (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1925).

Legends of Angria: Compiled from the Early Writings of Charlotte Brontë, edited by Fannie E. Ratchford and William Clyde De Vane (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933).

Five Novelettes, edited by Winifred Gérin (London: Folio Press, 1971). The Secret & Lily Hart: Two Tales by Charlotte Brontë, edited by William Holtz (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1979).

The Poems of Charlotte Brontë: A New Annotated and Enlarged Edition of the Shakespeare Head Brontë, edited by Tom Winnifrith (Oxford & New York: Blackwell, 1984).

The Poems of Charlotte Brontë: A New Text and Commentary, edited by Victor A. Neufeldt (New York: Garland, 1985).

An Edition of the Early Writings of Charlotte Brontë, edited by Christine Alexander, 2 volumes to date (Oxford: Blackwell, 1987- ).

The Belgian Essays, by Brontë and Emily Brontë, edited and translated by Sue Lonoff (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996). Collections The Life and Works of Charlotte Brontë and her Sisters, Haworth Edition, 7 volumes, edited by Mrs. Humphry Ward and C. K. Shorter (London: Smith, Elder, 1899-1900).

The Shakespeare Head Brontë, 19 volumes, edited by T. J. Wise and J. A. Symington (Oxford: Blackwell, 1931-1938).

OTHER “Biographical Notice of Ellis and Acton Bell,” in Wuthering Heights, Agnes Grey, together with a selection of poems by Ellis and Acton Bell, as Currer Bell (London: Smith, Elder, 1850).

LETTERS The Letters of Charlotte Brontë, with a selection of letters by family and friends, edited by Margaret Smith, 1 volume to date (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995- ).